Research from a team of SRI education researchers explored how augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR) have the potential to complement what special education educators do for students with dyslexia

SRI has been exploring how the effective use of technology can help students with special needs. Typically, only the most privileged struggling readers have access to effective, evidence-based curricula that aligns explicitly with their learning profile. Expensive 1:1 tutoring, although effective, is often not affordable or available.

But there is hope on the horizon…

Recent research from a team of education researchers at SRI International explored how augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR) have the potential to complement what special education educators do for students with dyslexia — potentially increasing the capacity of schools to accommodate more students.

Dr. Jennifer Yu, a Senior Principal Scientist and her team of researchers in the SRI Education division, leveraged what they know about research-supported interventions for students with dyslexia, and worked hand-in-hand with SRI technologists who specialize in vision technology. This combination of learning sciences expertise with vision technology experts led to a promising idea — with some promising emerging evidence.

The team created an early stage prototype AR experience for early primary grade students who have been identified as struggling readers. The experience was based on the Orton-Gillingham (O-G) instructional approach to reading and spelling that has been proven to improve literacy skills in students with diagnosed dyslexia and other struggling readers. O-G differs from conventional reading instruction in its focus on multisensory experiences (e.g., tactile, kinesthetic, visual, and audial), which makes it especially well-suited to AR.

However, O-G-based interventions require individual/small group instruction with experienced reading specialists that can be expensive and difficult to access. Existing efforts to embed O-G into affordable software programs are limited to visual and audio experiences. Augmented reality can achieve a true multi-sensory experience that most closely imitates an authentic O-G learning experience through kinesthetic, tactile, audio and visual tasks.

The team developed and tested the use of AR for one aspect of O-G, focusing on expanding phonemic awareness through an experience that is both fun, kinesthetic, and known to be effective.

The small pilot was conducted at an independent school that serves students in grades 1–9 who have been diagnosed with specific learning difficulties in reading and writing, such as dyslexia. Participating students were in grades 3 through 8. The project team was advised by their experienced and talented teachers, who provided guidance on topics including developing a literacy task that retained the integrity of the O-G approach, use of color and font, student engagement, and frequency of gamification elements and rewards.

The Student Experience

The design team selected the Microsoft Hololens because it is a high performance optical see-through augmented reality display, where the processing is on-board (no wires were tethered to a pc — though this experimental setup took advantage of the wifi capabilities of the Hololens), and it includes features such as human hand gesture recognition.

This head mounted display was complemented by extended reality software developed by the SRI vision technology team, using head and gaze tracking, real-time object detection, video analytics, and other capabilities. This platform enabled the development of multi-sensory tasks that support early literacy skills acquisition.

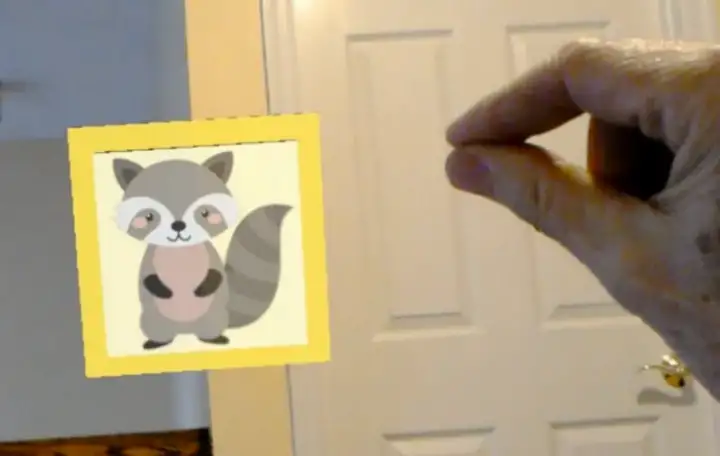

Following the principles of the O-G method, the student experience was visual, auditory, and kinesthetic. Students donned a Microsoft Hololens and began the activity with a practice session where they learned to (1) select an object in the virtual space by gazing at it, (a border around the object turned yellow when selected), and (2) choose among multiple objects by selecting an object by gazing at it and then using a pinching motion (see below photo). Students could choose from two layout options (letters on Scrabble-like tiles or letters embedded in a penguin character). They then participated in a phonemic awareness task using the word “SUN,” following auditory instructions delivered through the HoloLens. The activities included reading the word aloud, identifying the number of syllables in the word, matching phoneme sounds with the corresponding letters S U N, and differentiating the vowel and the consonants in the word.

As students completed each step of the sequence correctly, a virtual fireworks show appeared, and when they completed the whole task, students earned coins to place in a virtual coin jar. Students mastered the technology quickly (often more quickly than adults) and reported that the literacy experience was enjoyable. They also gave many suggestions to make the activity more engaging and comprehensible.

Early Insights

The work is in the earliest stages of concept evaluation, but the emerging evidence points to some important early insights:

● Student participation in the design process is critically important. Student ideas were shared frequently with the design team, leading to a much more effective solution. In addition, their feedback confirmed that students liked augmented reality, especially in a classroom setting: It is safer in that students can still see the real world around them, and it leaves the students’ hands free so they can gesture naturally.

“If it was VR, it would be strange to use this because if a teacher says something you can’t really see the teacher. It would make you feel weird because you don’t know where the voice is coming from. Augmented reality would work better in a classroom.”

● Older students benefit from AR, too. Many of the literacy activities that are currently used for struggling readers and students with dyslexia are designed for young children, which can be unappealing and even demoralizing for older students. Older students (upper primary grades) in this study confirm that XR may provide a great way to get older students with dyslexia engaged in literacy activities.

● Focus on supplementing instruction at school. One of the earliest questions facing the design team was, “What is the target market — homes or schools?” The study confirmed that while AR can be a useful supplement to instruction, it shouldn’t replace instruction. In that regard, the advisors felt that this is technology that should be used by teachers or specialists, and not as a product geared for home use.

● Improving the special education capacity of schools. We know that struggling readers learn best in 1:1 or small group settings, but not all schools can offer these much-needed services. The specific O-G task that was tested validates that AR could be used to provide individualized practice / reinforcement of concepts already taught by their teacher or tutor. Using AR can support teachers and students by offering engaging reinforcement of evidence-based multi-sensory reading instruction, particularly for students who need additional, targeted practice to become fluent readers.

This is just the beginning, and with new technology advancements, the potential grows. For example, the new Hololens 2 features a larger field of view, the ability to recognize individual fingers and more gestures, reduced and better distribution of headset weight (important for younger students), and the ability to manipulate holograms (e.g., move an object anywhere in the field of view).

For students with dyslexia, this demonstration project at SRI serves as a beacon of possibility: Says Dr. Yu, “Too often, students with disabilities are thought of as the outliers when considering solutions to advance learning. But in reality, some of our most useful and ubiquitous innovations, like speech recognition and eye gaze tracking, started out as a response to the needs of people with disabilities. If we really hope to make augmented reality an effective and lasting educational tool, then we must recognize that the needs of students with disabilities are not a corner-case, but rather their needs can serve as the innovation spark that elevates educational experiences for all learners.”

Authors: Jennifer Yu, Sc.D and Betsy Davies-Mercier, Ph.D., (SRI Education) in collaboration with Jim Vanides, M.Ed. (Senior Education & Industry Consultant)