Citation

Park, Y. (2020, March 3). When students don’t feel safe in the neighborhood: How can schools help? D.C. Policy Center.

Abstract

In D.C., a large share of children and youth up to age 17 are likely to be exposed to traumatic events: 21.3 percent have been exposed to an adverse childhood experience (ACE), [1] including an estimated 9 percent who have been a victim or witness to neighborhood violence. [2] Community violence is a common example of childhood adversity, which is a broad umbrella term for a range of circumstances that pose a serious threat to a child’s behavioral and mental well-being. [3] Community violence often happens without warning, which can cause feelings of sudden, horrifying shock and loss of control and safety. It involves intentional acts to harm others, which can lead to feelings of extreme mistrust of others and powerlessness.

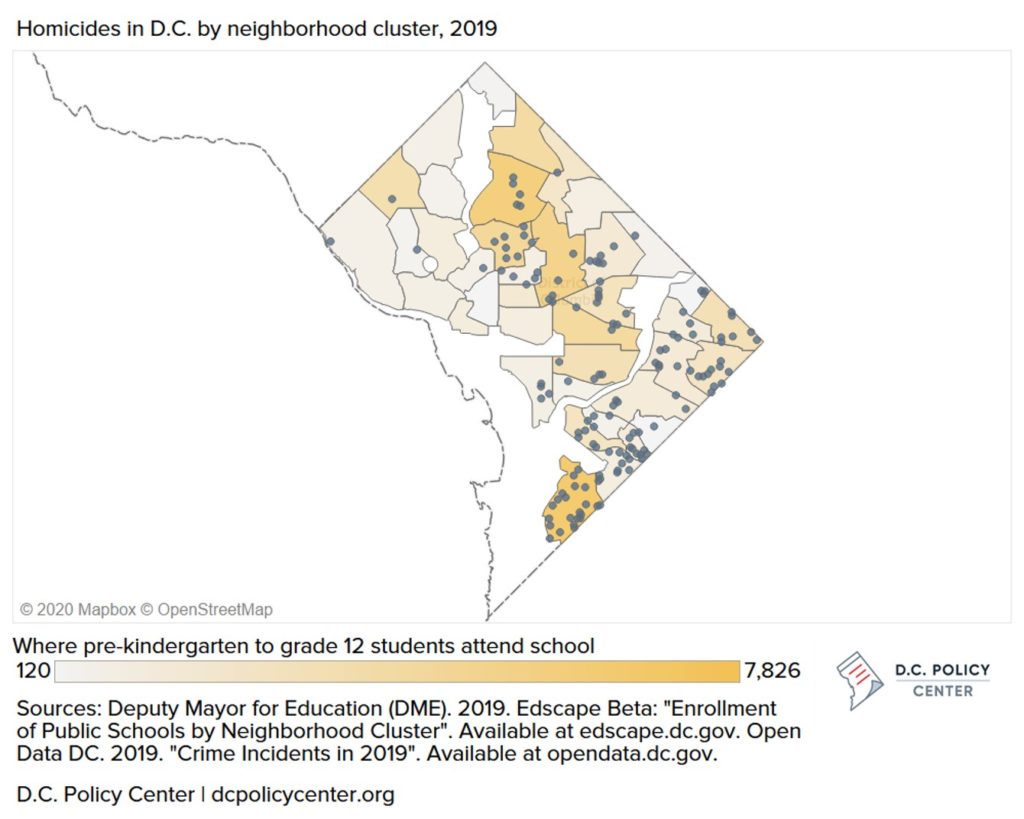

Some students are likely to be directly or indirectly affected by community violence in D.C., where the number of homicides increased to 166 in 2019, up by four percent over the previous year. Some neighborhoods have very high numbers of both homicides and public school students: the Congress Heights, Bellevue, and Washington Highlands neighborhoods had 25 homicides in 2019 and almost 8,000 public school students attending their schools. And that year, an estimated 19 shootings took place during the day within a block of a public school in D.C. [4]

Locally and across the U.S., there is an urgent need to support students who experience ongoing violence in the community, which is one of 12 distinct types of potentially traumatic events identified by the National Child Traumatic Stress Network.

Source: Student Behavior Blog

Below are four key strategies that educators can consider to mitigate the negative impact of trauma and community violence on students’ social-emotional, behavioral, and academic outcomes.

Best practices for school-based supports

1. Build strong relationships with students using a trauma-informed perspective

Trauma changes our brain, body, and how we interact with and react to the world and people around us. Trauma symptoms may look like a lot of different things—for example, “acting out,” disruptive behaviors, withdrawal from social life, or fidgeting in class—so most teachers may not even realize that a student is struggling with traumatic stress. School staff should become educated about the symptoms of trauma and prepared to respond in an appropriate and trauma-informed way. For example, teachers should have clear behavioral expectations coupled with compassionate, open communication with students in their classrooms to help create a sense of safety and security. Relatedly, it is helpful for teachers to maintain daily routines and activities as much as possible and try to avoid sudden changes. In addition, when teachers check in and converse regularly with students on topics like student interests and hobbies, they may better notice changes in their behaviors or mood that can indicate potential symptoms of trauma.

Research shows that social support and connectedness help to buffer the negative impacts of trauma and reduce distress,1213 as well as build an overall positive school and community environment. Schools that do this most effectively build staff knowledge and skills through professional development and a tiered approach to direct interventions, as described below.

2. Promote mental health and positive school climate

Students exposed to community violence can experience ongoing mental health challenges that disrupt their everyday school lives. Educators can prioritize mental health by conducting mental health screenings for students and providing ongoing education to staff and students about trauma, including how to find help or provide support to those in need. For example, in New York, one of the only three states (including Florida and Virginia) that mandate mental health education for students, there are organized mental health awareness days, teachers use the book “The Scarlet Letter” to teach lessons about stigma, and staff include mental health awareness tips in the morning announcements. For students who experience ongoing fear and anxiety due to community violence, a positive school climate can help them feel safe and secure.14 Positive school climates foster respectful, trusting, and caring relationships with clear and consistent rules and routines.

3. Use a tiered approach for evidence-based interventions

To systemically promote mental health and positive school climate, schools should strategically plan and implement tiers of evidence-based programs that integrate mental health and positive behavior and academic supports. Tiered frameworks generally refer to three tiers that correspond to different intensities of support, with tier 1 offering school-wide support for all students, tier 2 offering targeted supports for some students who may need more support, and tier 3 offering intensive supports for a few students who may need more support. Having this type of framework puts processes in place to identify, support, and monitor students’ progress and meet students where they are, with each tier including appropriate evidence-based programs that meet students’ social-emotional, behavioral, and academic needs.

4. Be prepared to respond to crises as they occur

Schools should be prepared with intervention and prevention plans that quickly bring students, families, and communities together in times of crises that can potentially have negative impacts on the mental and behavioral health, learning environment, and safety and security of students and educators. Forming crisis response teams at both the district and school levels with predetermined roles and responsibilities will establish a clear chain of command for effective coordination and management in the event of a crisis that impacts students, educators, and the community at large.

Resources to support mental health in D.C.’s schools

In school year 2018-19, D.C.’s traditional public and public charter schools had about 462 full-time mental health staff (269 licensed independent clinical social workers as well as psychologists and professional counselors) and about 127 part-time mental health staff, about half of whom are psychologists.15 All traditional public and public charter school teachers, principals, and staff employed by childcare providers are required to complete a behavioral health training every two years that prepares them to recognize symptoms of trauma and respond appropriately with positive behavioral interventions and supports (PBIS). Teachers and principals also complete courses on identifying at-risk students, the referral process, and suicide postvention every two years.

D.C.’s efforts to support mental health in schools generally follows a tiered framework. Tier 1 supports include mental health screenings and a 24-hour, seven-days-a-week telephone line staffed by behavioral health professionals who can activate mobile crisis teams, provide emergency psychiatric care, and help with problem solving. Tier 2 and 3 supports include targeted programs that work with students on the brink of homelessness, students who are committing status offenses, teen parents, and students experiencing a loss, life-threatening illness, violence, or other trauma.

D.C. Public Schools (DCPS) schools are required to develop a crisis response plan and create a central crisis team comprised of social workers, psychologists, counselors, and a designated lead. A central office provides annual training for members of the crisis team as well as other school leaders and provides tools to effectively support schools experiencing a crisis. Public charter schools are required to submit a School Emergency Response Plan to the DC Public Charter School Board.

Officials are piloting partnerships between public schools and community organizations that offer mental and behavioral health support to expand access to prevention, intervention, and treatment services and resources for students, as well as for teachers and parents. The goal of this program is to provide services to all of D.C.’s pre-kindergarten through grade 12 schools by school year 2023-24. Turnaround for Children also partners with DCPS and public charter schools to help school staff better understand brain science and how it affects students’ behavioral and academic outcomes.

In recent years, D.C. has expanded mental health services in schools with the Comprehensive Plan to Expand School-Based Behavioral Health Services, which emphasizes the importance of collaboration among schools, clinicians, and the community. Advocates, including school-based staff, are calling for additional supports to better meet the mental health needs of students in ways that are aligned with best practices and address school-adjacent issues affecting stress for students, such as community health, secure housing, criminal justice reform, or getting to school safely.

Additional resources

- How trauma affects the brain of a learner (Source: NPR) and Effects of trauma (Source: NCTSN): more information about the impact of trauma on the brain and body.

- Community Violence: Reactions and Actions in Dangerous Times (Source: NCTSN): help youth understand their reactions to community violence, how to stay safe, and when to talk with a trusted adult. Can be used with The Violent Places, Dangerous Times: Does Community Violence Control Your Life? checklist to provide questions for youth to determine if they have experienced community violence.

- Helping youth after community trauma: tips for educators (Source: NCTSN): helpful tips on identifying potential symptoms of trauma and how to help students.

- Helping your children manage distress in the aftermath of a shooting (Source: American Psychological Association, APA)

- The Role of Schools in Supporting Traumatized Students (Source: National Association of School Psychologists, NASP)

- Trauma Informed Care: Perspectives and Resources (Source: Georgetown University Center for Child and Human Development)

- How can we incorporate mental health education into schools? Consider the 5 T’s (Source: Student Behavior Blog): information on how to incorporate mental health education into schools.

- School Crisis Guide (Source: The National Education Association, NEA): information on preparing for a school crisis, including how to create a plan for your school and district.

- Psychological First Aid for Schools: Listen, Protect, Connect (Source: Ready.gov): helpful guide for teachers, administrators, and other school staff to help students in times of disaster, school crises, or emergencies.

- Youth Mental Health First Aid (Source: Mental Health First Aid): teaches adults how to help youth experiencing a mental health challenge or is in crisis.

- For more information about high-quality, evidence-based social-emotional learning (SEL) programs at each tier level, educators can refer to CASEL and the CASEL Program Guides; for a registry of evidence-based violence prevention and intervention programs, refer to the Blueprints for Healthy Youth Development. In addition, the Treatment and Services Adaptation Center for Resiliency, Hope, and Wellness in Schools has tested a number of tier 2 school-based interventions to reduce the effects of trauma in educational settings and offers free information and video-based training on the following:

- Cognitive Behavioral Intervention for Trauma in Schools (CBITS), a 10-week tier 2 group-based intervention delivered by school-based clinicians for middle and high schoolers with significant symptoms of trauma

- Bounce Back, a 10-week tier 2 elementary school-level version based on CBITS

- Support for Students Exposed to Trauma (SSET), a 10-lesson tier 2 curriculum designed to be implemented by teachers or school counselors with groups of 8-10 middle and high school students.

- For more information about what schools across the U.S. are doing to promote school safety, mental health, and violence prevention, refer to this map of school sites that have been supported by the Safe Schools/Healthy Students and Project Launch federal grants.

Endnotes

- ACEs, which refer to a specific subset of childhood adversities, is a term that was initially used in one of the largest studies of childhood abuse, neglect, and household challenges and later mental and physical health outcomes. See Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., … & Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American journal of preventive medicine, 14(4), 245-258.

- 2019 Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) data

- While community violence exposure was originally not included as an ACEs category, recent research supports the utility of doing so, given the link between community violence exposure to other ACEs and behavioral health needs later in life. See Lee, E., Larkin, H., & Esaki, N. (2017). Exposure to community violence as a new adverse childhood experience category: Promising results and future considerations. Families in society, 98(1), 69-78.

- D.C. Policy Center analysis of Open Data DC’s Crime Incidents in 2019 and Office of the Deputy Mayor for Education’s SY18-19 School Facilities Data.

- Shonkoff, J. P., Boyce, W. T., & McEwen, B. S. (2009). Neuroscience, molecular biology, and the childhood roots of health disparities: building a new framework for health promotion and disease prevention. JAMA, 301(21), 2252-2259.

- Borofsky, L. A., Kellerman, I., Baucom, B., Oliver, P. H., & Margolin, G. (2013). Community violence exposure and adolescents’ school engagement and academic achievement over time. Psychology of violence, 3(4), 381–395. doi:10.1037/a0034121

- McDonald, C. C., & Richmond, T. R. (2008). The relationship between community violence exposure and mental health symptoms in urban adolescents. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 15(10), 833-849.

- McGill, T., Self-Brown, S. R., Lai, B. S., Cowart, M., Tiwari, A., LeBlanc, M., & Kelley, M. L. (2014). Effects of exposure to community violence and family violence on school functioning problems among urban youth: The potential mediating role of posttraumatic stress symptoms. Frontiers in public health, 2, 8.

- Shonkoff, J. P., Boyce, W. T., & McEwen, B. S. (2009). Neuroscience, molecular biology, and the childhood roots of health disparities: building a new framework for health promotion and disease prevention. JAMA, 301(21), 2252-2259.

- Shonkoff, J. P., Boyce, W. T., & McEwen, B. S. (2009). Neuroscience, molecular biology, and the childhood roots of health disparities: building a new framework for health promotion and disease prevention. JAMA, 301(21), 2252-2259.

- Lynch, M. (2003). Consequences of children’s exposure to community violence. Clinical child and family psychology review, 6(4), 265-274.

- Scarpa, A., & Haden, S. C. (2006). Community violence victimization and aggressive behavior: The moderating effects of coping and social support. Aggressive Behavior: Official Journal of the International Society for Research on Aggression, 32(5), 502-515.

- Kliewer, W., Lepore, S. J., Oskin, D., & Johnson, P. D. (1998). The role of social and cognitive processes in children’s adjustment to community violence. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 66(1), 199.

- https://safesupportivelearning.ed.gov/safe-and-healthy-students/school-climate

- In addition to school-based strategies, the TraRon Center in D.C. was launched in 2018 as a space to help children exposed to gun violence through art and therapy, and D.C.’s Safe Passage program aims to get students to and from school safely.

Notes

- ACEs, which refer to a specific subset of childhood adversities, is a term that was initially used in one of the largest studies of childhood abuse, neglect, and household challenges and later mental and physical health outcomes. See Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., … & Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American journal of preventive medicine, 14 (4), 245-258.

- 2019 Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) data.

- While community violence exposure was originally not included as an ACEs category, recent research supports the utility of doing so, given the link between community violence exposure to other ACEs and behavioral health needs later in life. See Lee, E., Larkin, H., & Esaki, N. (2017). Exposure to community violence as a new adverse childhood experience category: Promising results and future considerations. Families in society, 98 (1), 69-78.

- D.C. Policy Center analysis of Open Data DC’s Crime Incidents in 2019 and Office of the Deputy Mayor for Education’s SY18-19 School Facilities Data.

- Shonkoff, J. P., Boyce, W. T., & McEwen, B. S. (2009). Neuroscience, molecular biology, and the childhood roots of health disparities: building a new framework for health promotion and disease prevention. JAMA, 301 (21), 2252-2259.

- Borofsky, L. A., Kellerman, I., Baucom, B., Oliver, P. H., & Margolin, G. (2013). Community violence exposure and adolescents’ school engagement and academic achievement over time. Psychology of violence, 3 (4), 381–395. doi:10.1037/a0034121

- McDonald, C. C., & Richmond, T. R. (2008). The relationship between community violence exposure and mental health symptoms in urban adolescents. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 15 (10), 833-849.

- McGill, T., Self-Brown, S. R., Lai, B. S., Cowart, M., Tiwari, A., LeBlanc, M., & Kelley, M. L. (2014). Effects of exposure to community violence and family violence on school functioning problems among urban youth: The potential mediating role of posttraumatic stress symptoms. Frontiers in public health, 2, 8.

- Lynch, M. (2003). Consequences of children’s exposure to community violence. Clinical child and family psychology review, 6 (4), 265-274.

- Scarpa, A., & H aden, S. C. (2006). Community violence victimization and aggressive behavior: The moderating effects of coping and social support. Aggressive Behavior: Official Journal of the International Society for Research on Aggression, 32 (5), 502-515.

- Kliewer, W., Lepore, S. J., Oskin, D., & Johnson, P. D. (1998). The role of social and cognitive processes in children’s adjustment to community violence. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 66 (1), 1999.

- https://safesupportivelearning.ed.gov/safe-and-healthy-students/school-climate

- In addition to school-based strategies, the TraRon Center in D.C. was launched in 2018 as a space to help children exposed to gun violence through art and therapy,and D.C.’s Safe Passage program aims to get students to and from school safely.

- D.C. Policy Center Fellows are independent writers, and we gladly encourage the expression of a variety of perspectives. The views of our Fellows, published here or elsewhere, do not reflect the views of the D.C. Policy Center.